Awkward dances, homemade brownies, and tentative first kisses – that’s all there in one school year is in The Perks of Being a Wallflower. The highly anticipated film was adapted from the same-titled novel by Stephen Chbosky, published over ten years ago in 1999.

What makes this film so different from others with similar teenage-modified plots? Was it destined to be yet another teen movie with the same cliched events that seem to fill the theatres with sappy annoyance and endings that make the audience want to pull its hair out with exasperation? Chbosky clearly strayed from that seemingly one-lane street by enhancing his nostalgic characters for viewers who have been waiting for years to see the beloved book on the big screen.

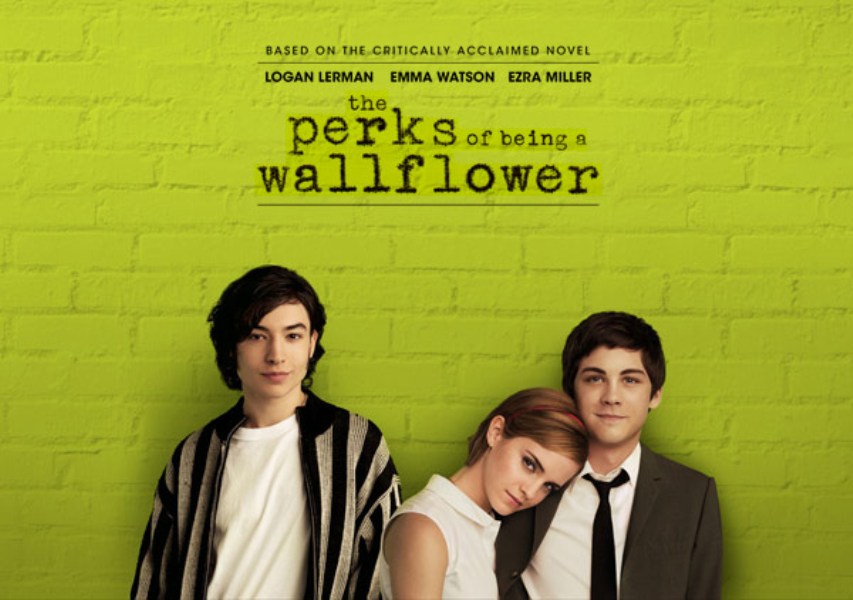

And who could deny Perks’ main trio the recognition they deserve? Introverted Charlie, played by Logan Leerman, opens with the first (on Aug. 25, 1991, to be exact) of many letters written to an anonymous reader as he begins his first days of high school while attempting to cope with the suicide of his best friend and the death of his favorite aunt. He is taken under Patrick’s wing, played by Ezra Miller, clearly the complete opposite of quiet Charlie. Unafraid to be the class clown as well as an open homosexual, “Nothing”, as the students call him, is the playful tone of movie with his spontaneity; yet he deals with his own sufferings as he longs to be with football star Brad who is too embarrassed to share his affection. The young woman who completes the odd triangle is the perky but damaged Sam, played by Harry Potter’s Emma Watson. Sam becomes Charlie’s first crush, and by events throughout the movie, is stuck between keeping her and everyone else happy.

Happy becomes undefinable as the young protagonist is made available to a world that before would have been something stopping him from “participating.” Charlie experiments with drugs, takes a ride in his first relationship, and, on a truck ride through a tunnel, discovers what it means to feel “infinite”.

Charlie is able to make connections with anyone he meets, especially Sam and Patrick’s friends. Instead of being outed as an anti-social nobody, Charlie shows that one of the perks of being a wallflower is that through watching the action behind the scenes, he notices the important things that tend to be overlooked.

One of those important things is that beneath the laughs and normal teenage rowdiness lies hidden truths more solemn than the characters let on in the beginning. Love that cannot be had leaves Patrick heartbroken after Brad’s father discovers them together. Love that cannot be found leaves Sam going for the lowers standards. And for Charlie, which isn’t revealed until the end of the movie, his quiet, estranged persona is caused by a pain with the relationship held with his aunt that he only dabbles at throughout the movie.

It is through them that even through the veil of irony, Chbosky brought these meaningful, misfit characters to life. This kind of raw vulnerability allowed the film to be relateable to viewers-and readers-of all ages as layer upon layer of confusion, heartache, and awkward was thrust upon them to analyze within themselves.